Michael Bloomberg's exit from the presidential race makes it more legally complicated for him to carry out his announced plan of spending millions of dollars to defeat President Trump.

Here is how an NBC news article summed it up:

"Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg's massive campaign apparatus and an army of some 500 staffers will march on through the general election in November even if he loses the Democratic nomination, campaign officials tell NBC News, shifting their efforts toward working to elect whomever the party selects to face President Donald Trump....Hawkfish, a digital company started by Bloomberg that's carrying out his $100 million online ad campaign, will be retained through Election Day to help defeat Trump, the officials said...If another Democrat wins the nomination, the Bloomberg-funded staffers won't work directly for the nominee, which would constitute an in-kind contribution by Bloomberg to the campaign that would exceed federal contribution limits. Rather, those staffers would be paid by an independent funding vehicle supported by Bloomberg, officials said. By law, those staffers and Hawkfish would not be able to coordinate their activities with the nominee's campaign."

The prohibition on coordination raises some difficult questions. Given how thoroughly enmeshed Bloomberg and his team are in mainstream Democratic politics, how will it even be possible to police whether the Bloomberg effort is or isn't coordinated? Short of the federal government electronically eavesdropping on Bloomberg or on a Democratic presidential campaign headquarters the way it did with Trump Tower and Trump campaign aides in 2000, authorities will have a hard time gathering evidence of coordination. Defining coordination will provide endless billable hours for election lawyers, while the actual operatives send and receive the necessary wink-and-a-nod signals anyway through interviews with reporters or other informal go-betweens.

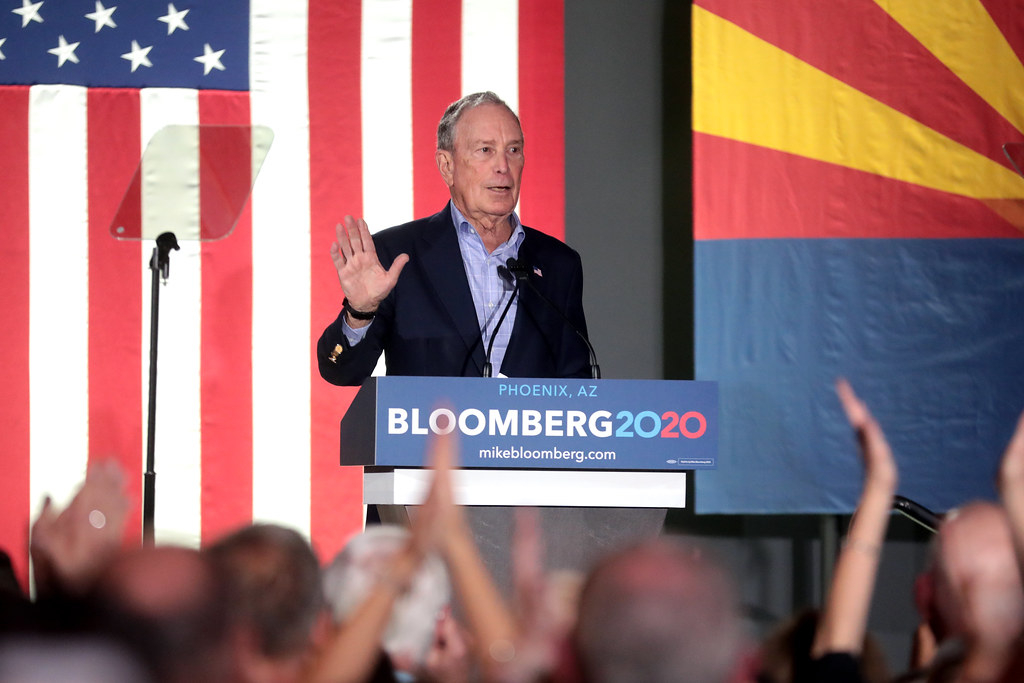

(Image source: Gage Skidmore/Flickr) |

Bloomberg's right to launch even a non-coordinated campaign exists largely thanks to a series of Supreme Court decisions that have defended the First Amendment against congressional assaults. Buckley v. Valeo in 1976, McConnell v. FEC in 2003, and Citizens United in 2010 all recognized that congressional restrictions on campaign spending conflicted with the Constitution's protection of the rights to speech, press, assembly, and petition.

This is a story I've been personally following closely now for more than two decades. Here is a 2001 Smartertimes post criticizing the New York Times for trying to prevent, on "coordination" grounds, the Republican National Committee from airing ads backing the Republican candidate for governor of New Jersey. As I put it then, "More speech is better. It makes for a healthier debate, a more informed electorate, a more vigorous airing of the issues. It prevents arbitrary line-drawing by government authorities deciding who can speak during an election and who can't." That same year I reviewed for the Wall Street Journal Bradley Smith's book Unfree Speech: The Folly of Campaign Finance Reform.

Ironically, the candidate Bloomberg would spend money to elect, Joe Biden, says that, if elected, a President Biden would outlaw precisely that sort of spending. Biden's campaign website says "Biden will introduce a constitutional amendment to entirely eliminate private dollars from our federal elections. Biden believes it is long past time to end the influence of private dollars in our federal elections. As president, Biden will fight for a constitutional amendment that will require candidates for federal office to solely fund their campaigns with public dollars, and prevent outside spending from distorting the election process." The other leading Democratic presidential candidate, Bernie Sanders, has his own proposed Constitutional amendment to rewrite the First Amendment in a way that allows restrictions on campaign spending.

The campaign finance "reform" that is consistent with expanding freedom and with the principles of the First Amendment is to let the donors and their operatives talk to, or even "coordinate with," whomever they want. Those First Amendment principles apply to Mike Bloomberg, George Soros, Tom Steyer, and S. Donald Sussman spending for the Democrats. They apply equally to Sheldon and Miriam Adelson and Richard and Elizabeth Uihlein spending for the Republicans.

The argument against coordination is allowing it essentially permits unlimited campaign contributions, which potentially have a corrupting influence. "Reduce the corrupting influence of money in politics," is the way the campaign website of Biden puts it. Candidate Biden himself spent last night at a fundraiser in Bel Air, California, that, according to a pool report from Seema Mehta of the Los Angeles Times, was held in the backyard of Sherry Lansing's 10,043 square foot home with six bedrooms and seven bathrooms that last sold in 2005 for $15 million. Perhaps if Biden could coordinate with Bloomberg, he's have to spend less of his time and energy running around to the homes of people like Lansing, who can gather and host 350 $1,000-level or $2,800-level donors on her estate. In any event, Bloomberg's campaign, like Steyer's, demonstrated that all the money in the world can't buy political success, with the possible limited exception of American Samoa.

If a congressional fix is needed to make it clear coordination is allowed, let Congress act swiftly to provide it. The Senate side should be no problem — the majority leader, Mitch McConnell, was the name plaintiff in McConnell v. FEC and has had a distinguished career as a principled defender of campaign speech and First Amendment principles. As for Speaker Pelosi, presumably she understands that Bloomberg wants a Democratic Congress, too. One of the many virtues of money in politics is its ability to break legislative gridlock and to lubricate bipartisan cooperation.